By Holly Honderich

BBC News, Washington

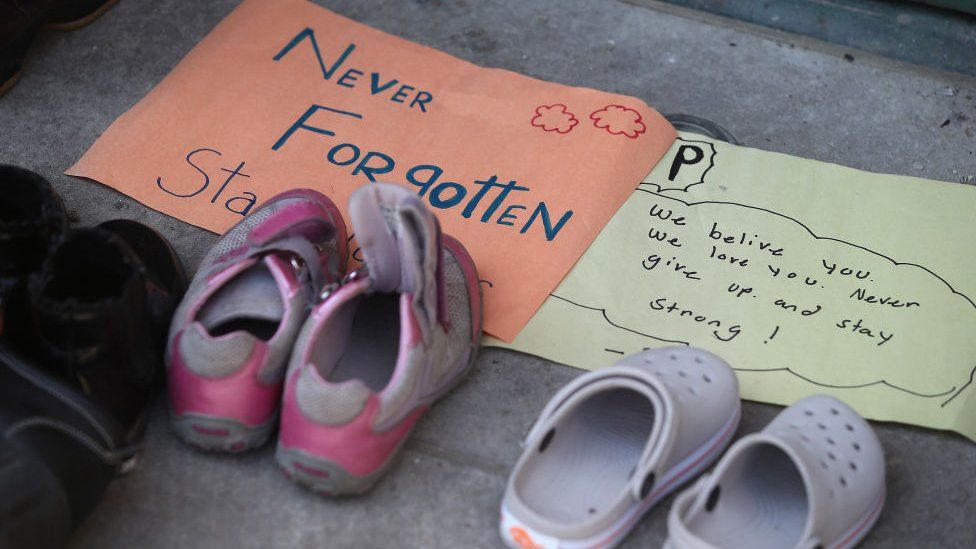

The discovery in May of the remains of 215 Indigenous children – students of Canada’s largest residential school – prompted national outrage and calls for further searches of unmarked graves.

Since then, more unmarked gravesites have been found, providing previews of investigations by Canada’s First Nations into the deaths of residential school students.

A rising tally of these graves – more than 1,100 so far – has triggered a national reckoning over Canada’s legacy of residential schools. These government-funded boarding schools were part of policy to attempt to assimilate Indigenous children and destroy Indigenous cultures and languages.

Here’s what we know about the findings so far.

What do we know about the 215 graves?

In May, Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Chief Rosanne Casimir announced that the remains of 215 children had been found near the city of Kamloops in southern British Columbia (BC) as part of a preliminary investigation.

Some of remains are believed to be of children as young as three.

All of the children are believed to have been students at the Kamloops Indian Residential School – the largest such institution in Canada’s residential school system.

The remains had been confirmed with the help of ground-penetrating radar technology, Chief Casimir said, following preliminary work on identifying the burial sites in the early 2000s.

The full report into the remains found is due on Thursday, and the earlier findings may be revised. Indigenous leaders and advocates have said they expect the 215 figure to rise.

“Regrettably, we know that many more children are unaccounted for,” said Chief Casimir in a statement.

Thousands of children died in residential schools and their bodies rarely returned home. Many were buried in neglected graves.

To this day there is no full picture of the number of children who died in residential schools, the circumstances of their deaths, or where they are buried. Efforts like those of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation and others are helping to piece some of that history together.

The Kamloops school, which operated between 1890 and 1969, held up to 500 Indigenous students at any one time, many sent to live at the school hundreds of kilometres from their families. Between 1969 and 1978, it was used as a residence for students attending local day schools.

Of the remains found, 50 children are believed to have already been identified, said Stephanie Scott, executive director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. Their deaths, where known, range from 1900 to 1971.

But for the other 165, there are no available records to mark their identities. Children “ended up in pauper graves,” Ms Scott said. “Unmarked, unknown.”

What about the other sites?

In June, the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan announced it had found an estimated 751 unmarked graves after a similar investigation – the largest such discovery to date. The remains were found near the former Marieval Indian Residential School, which operated from 1899 to the 1990s and under the control of the Roman Catholic Church for much of that time.

Cowessess leaders have not yet determined if all the unmarked graves belonged to former students. Technical teams will continue the investigation to provide verified numbers.

Cowessess Chief Cadmus Delorme emphasised that the discovery was of unmarked graves – not a mass grave site – and suggested that the Catholic Church may have removed grave markers at some point in the 1960s.

A week later, the Lower Kootenay Band in British Columbia said the remains of an additional 182 people had been found near the grounds of the former St Eugene’s Mission School. St Eugene’s was operated by the Catholic Church from 1912 until the early 1970s.https://emp.bbc.com/emp/SMPj/2.43.6/iframe.htmlmedia caption”No reconciliation without truth”: A survivor recounts abuse in Canadian residential school

And in mid-July, the Penelakut Tribe in British Columbia said it had identified some 160 “undocumented and unmarked graves” on their grounds and foreshore near the former site of the Kuper Island Industrial School. They offered few details, though the tribe has been working with researchers in recent years to find potential gravesites.

What are residential schools?

The Kamloops residential school was one of more than 130 others like it. The schools were operated in Canada between 1874 and 1996.

A linchpin in the government’s policy of forced assimilation, some 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children were taken from their families during this period and placed in state-run boarding schools.

The policy traumatised generations of Indigenous children, who were forced to abandon their native languages, speak English or French and convert to Christianity.

Christian churches were essential in the founding and operation of the schools. The Roman Catholic Church in particular was responsible for operating up to 70% of residential schools, according to the Indian Residential School Survivors Society.

“It was our government’s policy to ‘get rid of the Indian’ in the child,” said former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations Perry Bellegarde. “It was a breakdown of self, the breakdown of family, community and nation.”

Timeline: The key dates

Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A Macdonald, authorises the creation of a residential school system, established by Christian churches and the federal government, with the intent to assimilate indigenous peoples in Canada.

Residential schools are made compulsory for children from age seven to 15. Some 150,000 First Nations, Metis and Inuit children are eventually taken from their homes, with many parents surrendering them under threat of prosecution.

The residential school system begins to wind down – though the last school will close in 1996 – as the psychological and cultural impacts of the schools come under growing scrutiny.

An estimated 6,000 children die at the schools, according to the former chair of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission Murray Sinclair. They die from causes like disease, neglect, or accidents. Physical and sexual abuse is also common.

There is still no full picture of the number of children who died or where many of them are buried.

Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper issues a formal apology for the residential school system, which saw over 130 such institutions operating across Canada.

“Today, we recognise that this policy of assimilation was wrong, has caused great harm, and has no place in our country,” he says.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada releases its final report on the legacy of residential schools and describes the central policy behind the system as one of “cultural genocide”. It recommends funding to find burial sites and commemorate the children who died away from home.

Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc First Nation in British Columbia announces that a preliminary investigation, using ground penetrating radar, has found an estimated 215 unmarked graves at the site of a former residential school. Other First Nations in Canada are conducting similar research.

The landmark Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report, released in 2015, detailed sweeping failures in the care and safety of these children, and complicity by the church and government.

“Government, church and school officials were well aware of these failures and their impact on student health,” the authors wrote. “If the question is, ‘who knew what when?’ the clear answer is: ‘Everyone in authority at any point in the system’s history.'”

Students were often housed in poorly built, poorly heated, and unsanitary facilities, the report said. Many lacked access to trained medical staff and were subject to harsh and often abusive punishment.

The squalid health conditions, the report said, were largely a function of the government’s resolve to cut costs.

“We have records in our archives of school administrations arguing with the Indian affairs government at the time about who was going to pay for the funerals of students,” Ms Scott said. “They would do it all at minimal expense.”

What do we know about the search for missing children across Canada?

Research by the TRC found that thousands of Indigenous children sent to residential schools never made it home.

Physical and sexual abuse led some to run away. Others died of disease or by accident amid neglect. As late as 1945, the death rate for children at residential schools was nearly five times higher than that of other Canadian schoolchildren. In the 1960s, the rate was still double that of the general student population.

“Survivors talked about children who suddenly went missing. Some talked about children who went missing into mass burial sites,” said former TRC chair Murray Sinclair in a statement in May.

Other survivors spoke of infants fathered by priests at the school, taken from their mothers at birth and thrown into furnaces, he said.

The TRC identified 3,200 confirmed deaths, though it noted that the work of identification and commemoration was “far from complete”. Mr Murray estimated some 6,000 children may have died.

What has been done?

In 2015, the TRC issued 94 calls to action, including six recommendations regarding missing children and burial grounds. Prime Minister Trudeau promised to “fully implement” all of them.

- According to a running count by the CBC, 10 of the projects have been completed, 64 are in progress and 20 have not begun

- The TRC, struck in 2009, fought for the issue of unmarked burial sites to be included in its mandate

- In 2019, the government committed C$33.8m ($28m; £19.8m) over three years to develop and maintain a school student death register and set up an online registry of residential school cemeteries

- So far, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation says it has received just a fraction of this money though “discussions are ongoing”

What has been the reaction?

In early July, Mr Trudeau visited Cowessess First Nation and said it was “shameful” that children died because of residential schools and the “legacy of inter-generational trauma” caused by the policy.

Ms Scott, along with Chief Bellegarde and other Indigenous leaders, have pressed the government for a thorough investigation of all 130 former school sites to find any unmarked graves.

“Trudeau has been willing to move on this, he’s got a lot of words, but we really need to see action,” said Ms Scott.

The discoveries also cast a shadow over the country’s 1 July Canada Day holiday. Municipalities across Canada called off celebrations this year in recognition of the findings.

The preliminary findings have also renewed demands for an apology from the Catholic Church – one of the calls to action in the TRC report.

In 2017, Mr Trudeau asked Pope Francis to apologise for the church’s role in running Canada’s residential schools – but the church has so far declined.

The United, Anglican and Presbyterian churches issued formal apologies in the 1980s and 1990s.

News of the BC discovery also spurred a global response, prompting statements from Human Rights Watch and the United Nations.