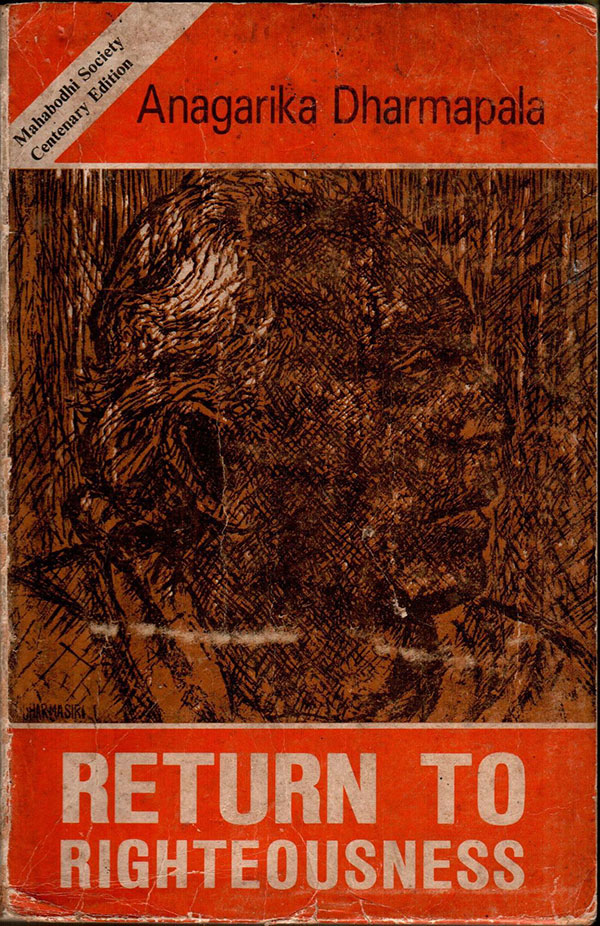

“I have to be active and activity means agitation according to constitutional methods.”

—Anagarika Dharmapala

INTRODUCTION

The Commemoration of a National Hero

CEYLON, with her twenty-five centuries of recorded history, is endowed with a generous quota of national heroes who are gratefully

remembered by the people for the wars they fought for national independance, the movements they sponsored for the welfare of the masses, the books they wrote, the monuments they erected and the contributions they made to the individuality and richness of the national culture. The heroes of ancient times whose fame lives in legends and songs, in folk-tales and chronicles, have acquired for themselves in the minds of the people an image which has remained unaltered for centuries. So indelible is the impression thus created in their minds that even a critical student of history—not to speak of a cynic or a sceptic—runs the risk of courting popular disapproval if anything which deviates, though very slightly, from the popular image were to be said or written. This is not an attitude of mere apotheosis. To a Sinhala, Dutugemunu, Parakramabahu, Madduma Banda, Keppetipola, &c. are not deities or super-men, to be veneraterd or appeased on account of any super-natural power or ability they are believed to possess. These men are honoured and remembered for the greatness they displayed through piety, patriotism or bravery and for the sacrifices they made for their honour or their motherland.

In a country, which honours her national heroes of olden days in diverse ways and pays them the highest compliment of being regarded as models worthy of emulation, one would expect a continuing awareness of the need to maintain records of the thoughts, deeds and achievements of her recent heroes and to preserve for posterity their homes and belongings. One would, at least, expect to see wellwritten biographies and collections of letters and writings of such persons. Though recently several national heroes of modern times were commemorated by the erection of their statues in the capital and elsewhere, the nation is kept informed of their services and their claims to greatness only by short articles in the local press which appear usually on their death anniversaries. The result of such halfhearted attempts to keep the memory of our national heroes alive is all too evident whenever public meetings are held in their honour. One is often disappointed to find that men, whose services to the nation had been invaluable and whose efforts had made millions happy and prosperous, are remembered by only a diminishing group of

people who had been close to them or are bound by family ties. This, indeed, is not a happy state of affairs. As an old saying goes, a nation can be called a living nation only as long as it honours its dead.