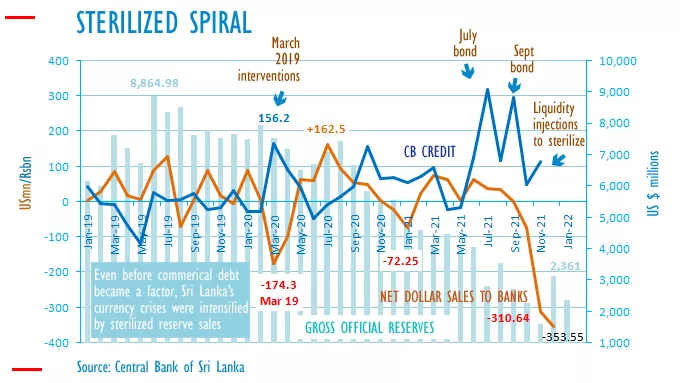

ECONOMYNEXT – Sri Lanka’s foreign reserves sales to commercial banks defend a 200 to the US dollar peg soared to 736 million dollars from September to November 2021 official data shows, forcing money to be printed to maintain a fixed policy interest rate.

In November and December alone 664 million dollars of reserves were sold to commercial banks.

The injection of money after such ‘reserves for imports’ to defend a peg (sterilization of interventions) prevents the contraction of reserve money, prevents a rise in short term interest rates, prevents a required slowdown in private credit and re-ignites demand for imports.

In a remarkable descent in to Mercantilist ideology, calls were made in Sri Lanka to spend more reserves on imports while simultaneously claims were made that a 200 to the US dollar peg was unsustainable.

Related

Sri Lanka use of reserves for imports is a deadly false choice: Bellwether

Why Sri Lanka’s rupee is depreciating creating currency crises: Bellwether

Any reserve sales for imports is a defence of the peg, which commits a central bank with a fixed policy rate to print more money through ‘open market operations’, triggering yet more imports.

If reserves are used for imports without allowing the monetary base to fall, sovereign as well as private foreign debt default may become inevitable even if debt is re-structured, analysts have warned.

The injection of money after giving reserves for imports is the hallmark of a soft or unstable peg (now called a ‘flexible’ exchange rate), that trigger currency crises and balance of payments deficits.

A clean float (suspension of convertibility) is required to stop the cycle of sterilized interventions.

Sri Lanka required structurally higher interest rates as soon as the country was locked out of bond markets in 2020 to generate resources to repay debt. However rates were cut in 2020 amid downgrades.

Sri Lanka’s market rates have risen after yield controls were lifted, though mostly three month bills are being bought, and deficit monetization is minimal.

In sterilizing reserves for imports, liquidity is injected into commercial banks (private sector) but to later observers it appears as deficit finance, since money is printed not against private securities but government debt.

For centuries, during the gold standard era, the Bank of England used to operate its discount rate (which was not fixed) against private debt (bankers’ acceptances) which were tradable in the secondary market.

Open market operations as known today was invented by the Federal Reserve in the course of firing the ‘Roaring 20s’ bubble that led to the Great Depression. A part of the bubble involved firing up stocks with margin credit.

In the way Sri Lanka’s central bank engages in reserve sales for debt repayments against newly created Treasury bills it is possible to appropriate reserve for debt repayment without changing rupee reserves in individual banks through a series of back-to-back transactions (no reserve pass-through).

Sri Lanka created a soft-peg in 1950 ending floating short term rates and a fixed exchange rate that had protected the population from a Great Depression and two World Wars. Sri Lanka has reserves worth 11 months of imports when the soft – peg was created.

The UK around the time was facing severe currency troubles due to Keynesianism.

In November the central bank sold 310 million US dollars to commercial banks on a net basis which rose to 353 million US dollars by December.

The interventions are the highest seen since the 2018 currency crisis.

Sri Lanka’s past currency crises up to around 2005, which sent the rupee careening down from 4.70 to the US dollar to around 110 were intensified with sterilized reserve sales to defend a peg, though the crisis may have been initially triggered by budget finance or rural credit.

Amid more discretionary and contradictory monetary policy after the end of a 30-year war, involving a ‘flexible’ exchange rate and ‘flexible’ inflation targeting Sri Lanka has faced currency crises and depreciation in quick succession and the rupee is now at 200 to the US dollar.

Parallel exchange rates are around 248 to the US dollar.

The central bank has also imposed surrender requirement for exporter and remittance dollars, despite the peg being weak and requiring tighter monetary policy. A surrender requirement pushes the currency down through liquidity creation. A reserve sale can strengthen the currency as long as it is not sterilized.

In the nine months to September the central bank bought 228 million dollars on a net basis from commercial banks under a surrender requirement despite a peg having already weakened. (Colombo/Feb08/2022 – Update II)